Happy New Year! Maybe the end of every year evokes such feelings, but it seems that a lot of people are very happy that 2012 is behind us. Maybe it was the incessant bickering of the U.S. elections. Maybe it was the constant reminders in the media that the global economy is in trouble. Huge tragic events, both natural and manmade, also helped to taint our perceptions about the world’s state of affairs. The ubiquitous attention and analysis of the so-called “Fiscal Cliff” no doubt raised doubt in the minds of many. Even the oft-prophesied “end of the world” possibility (this time thanks to the Mayan calendar), might have increased some folks’ level of anxiety toward the end of the year. Yet, here we are in January having dodged all of the dire outcomes fussed and fretted about all year. The stock market logged impressive returns for the year. The economy continues to grow with noticeable improvements in the long-moribund areas of housing and employment. Still, despite all of the good news out there, a simmering, palatable sense of dread permeates much of what we hear and see – whether on the nightly news or at the water cooler. Why are people afraid now, and what can be done to ease these concerns? Let’s tackle these issues after the review.

Fourth Quarter Review

For the quarter, stock market returns were a mixed bag, with Europe and the emerging economy markets performing the best. A sense that Europe has seen the worst of the current economic downturn and that some light can be seen ahead may have been a key reason for this strong showing. For the year, nearly every index generated returns well above long-term averages. In the final analysis, many of the worries which dominated the headlines during the course of the year (Euro-implosion, China slowdown, disappointing corporate earnings, U.S. “Fiscal Cliff,” etc.) seemed to scarcely affect equity returns. Even in the U.S., where the excessive drama associated with the presidential election did little to stem the markets’ mostly upward climb.

Fixed income securities lagged equities in the quarter, but continued to show positive returns as investors are convinced that higher interest rates are unlikely in the face of the Fed’s pledge to keep them low. The latest plan for quantitative easing has only reinforced this conclusion. During the quarter, retail investors continued to pile into bond funds at a near-record pace. Despite the positive returns in stocks for the year, there was little evidence that retail investors added to equity exposure in the quarter.

Here’s what the fourth quarter looked like by the numbers:

| Index | 4th Qtr 2012 | Year to Date | Trailing 12 Months |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dow Jones Industrial Average | -1.7% | 10.2% | 10.2% |

| S&P 500 | -0.4% | 16.0% | 16.0% |

| NASDAQ | -3.1% | 15.9% | 15.9% |

| Russell 2000 | 1.9% | 16.4% | 16.4% |

| MSCI EAFE | 6.6% | 17.9% | 17.9% |

| MSCI EAFE Small Cap | 6.1% | 20.4% | 20.4% |

| MSCI Emerging Markets | 5.6% | 18.6% | 18.6% |

| Barclays Aggregate Bond | 0.2% | 4.2% | 4.2% |

| Barclays Municipal Bond | 0.7% | 6.8% | 6.8% |

| Dow Jones Commodities | -6.5% | -2.1% | -2.1% |

Big Scary Things That Never (or Rarely) Happen

We can only imagine the response early humans must have had to the first solar eclipse. The sun, perhaps the only significant light source these people had ever known, begins to dim and then suddenly all but disappears. What could they think? The ancient Chinese believed that a dragon was devouring the sun. The Greeks viewed a solar eclipse as a bad omen, a sign that the gods were angry. Herodotus records a battle between the Lydians and Medes that was interrupted by a sudden darkness on the field. The armies instantly stopped fighting and made peace with each other because of this celestial display.

The good news for early man was that solar eclipse did not last long. Yet, we wonder how many prayers and sacrifices were offered following an eclipse to appease the displeased gods. How many people sat around and worried about the next eclipse and what might happen if, the next time, the sun did not return.

We may chuckle a bit at the unsophisticated notions of our progenitors, yet we can see this kind of behavior still today on the part of well-educated and intelligent people as it applies to the economy, the capital markets and politics. Normal people tend to fear things that are too big to deal with, events that make them feel out of control and circumstances that lead to a feeling of helplessness. Feeling bad or fearful, in and of itself, is perfectly normal. How we deal with this fear, and the actions to which it may lead us, may have a huge (and often negative) impact.

“Armageddon” and Other Scary Movies

Hollywood knows audiences love to be scared. From 1922’s “Nosferatu” to the latest edition of “Texas Chain-Saw Massacre,” the horror genre is well-ingrained in our culture and psyche. Novelist Stephen King explains in his essay “Why We Crave Horror Movies” our fascination with the scary movie. “We like to prove to ourselves that we can handle it, and it brings us out of the gray areas of adulthood to the black and whites of childhood.” In the horror flick, good and evil are clearly delineated, and in most cases the good guys win. We also know that the movie (and our feelings of fear) will end and we will find ourselves again in a comfortable, warm theater among our peers.

A popular sub-category of the horror film is the “disaster movie.” In these, the “scary monster” is replaced with some huge natural or man-made disaster. Instead of the “gotcha!” moments ubiquitous in the standard horror fare, the disaster movie relies on a slow grind of event after event pulling the characters toward their certain doom. The most effective movies in this subgenre were those that could show the protagonists, despite the odds being stacked against them, overcoming the most horrific situations. The pinnacle (if that is the right word) of this type of movie, in our view, is the Michael Bay-directed 1998 film “Armageddon.”

The disaster in this movie was a massive asteroid on a collision course with Earth. Can you imagine anything scarier? We won’t spoil the ending (you can probably imagine how it ends anyway), but we would note that it was the highest grossing movie of that year. People love to be scared!

The fear generated by a disaster movie is subtly different that the more traditional horror offering. Due to the bigger, more general nature of the “horror” the characters (and perhaps the audience) feel helpless, hopeless and doomed despite anything they might do. The characters’ ability to avoid the worst-case scenarios (which may seem to be a fait accompli) by the end of the movie provides the audience with the closure and comfort they could not imagine during the movie.

“It’s the End of the World, and This Time I Mean it!”

It seemed that 2012 had more than its fair share of doomsday scenarios. And unlike the temporary fear we experience watching a movie, fear from these dire forecasts can have generated lingering and lasting effects. From the California preacher, Harold Camping (who predicted the end of the world twice last year – May 21st and October 21st) to the much-more-widely-publicized-than-it-needed-to-be Mayan calendar (which “predicted” the end to come December 21st), last year was, in many ways, a highpoint of spectacularly wrong predictions. The Eurozone failed to implode. Greece is not only still here, it’s still a part of the EU. Despite near-universal bullishness on gold, the shiny commodity underperformed most assets. Like the old saying goes, “It’s difficult to make forecasts, especially about the future.”

The election cycle in the U.S. also saw its share of bad predictions. Anyone who closely followed the polls could have concluded that the presidential election looked a lot closer than the final tally would indicate. The political debate landscape is littered with numberless really bad opinions about election outcomes; who would run or not run; and the likelihood of certain laws being passed. In the end, the winners won and the nation still remains intact. Even the hyped-beyond-all-reason “Fiscal Cliff” phenomenon turned out to be just slightly more interesting than the Mayan calendar.

Last year’s fascination with really big, scary things (that ultimately didn’t happen) might be attributable to the simple notion that people like to be scared. On the other hand, it may be that the tenor of political debate in this nation has tainted our perception of the consequences of choice. “You like candidate X and I like candidate Y, let’s shake hands and still be friends” seems to have been replaced with “if you vote for candidate X, __________ (insert pet big scary thing) will happen.” A full election cycle of such “debate” constantly in our ears and eyes may have conditioned us to expect big scary things, or maybe even secretly hope for the end of the world, if for no other reason to escape the cacophony of this acrimonious political dialogue.

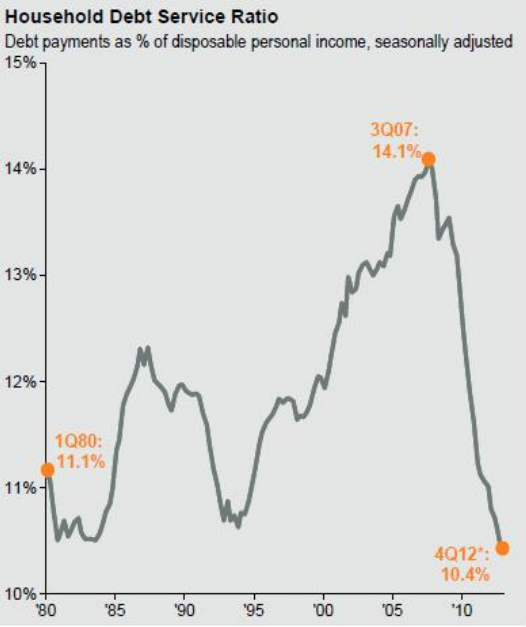

Whatever the reason, this negativity has been prevalent in the capital markets as well. There was a time when bull markets could be celebrated and actually enjoyed. We can’t remember a year so dour and sour where the S&P returned 16%. Even now, we hear people (either in person or in the media) speak of the “current recession” or the “difficult investment environment.” Perhaps we are still dealing with the deep scars acquired in the 2008-2009 global financial crisis. Perhaps the malfeasance of a few bad actors (Bernie Madoff, Allen Stanford, et al.) has soured the public on the notion that the capital markets can still provide the average investor with attractive returns. Yet, we cannot help but marvel at the still-negative tone of economic and capital market commentary after nearly four years of a bull market, fourteen consecutive quarters of positive GDP growth, three years of positive employment growth, a massive de-leveraging of U.S. household balance sheets and three years of solid, if not stunning, U.S. corporate profit growth. Even a measurable recovery in the housing market (home builder sentiment at a seven-year high, for example), has been met with only tentative, tepid applause.

Successfully Dealing with Fear Can Improve Investment Returns

When we experience fear, the primitive, feral part of our brain takes over and quickly shifts us into “fight or flight” mode. In the face of immediate and real physical danger, this response serves us well. In the face of perceived danger (the only kind we actually face in the capital markets), it proves much less effective. In fact, it may not be a stretch to suggest that the worst investment decisions people ever make happen when they are afraid. When an investment asset we own declines in value, we begin to fear it will go down further. The feral section of our brain seems incapable of imagining this investment reversing course and ever appreciating in value. This fear propels us to do something. Unlike the fear caused by a physical danger where we instinctively pick up something to defend ourselves or pick up our heels and run away, fear in the capital markets tends to make us want to sell. We feel the need to do something and only selling will prevent our asset from declining further.

Selling may also calm the fear that had gripped our hearts only moments ago. After selling is when the more rational part of our brain regains control and we begin to perform all sorts of analyses on the situation. Feeling safe with cash in the investment account (note the irony…), we tell ourselves we will re-invest as soon as things clear up a bit. Lo and behold, things do calm down a bit, but we feel reluctant to invest now because the market has moved higher. We then tell ourselves we will wait for a correction before committing our cash to the market. Those who sold their investments while in the grip of fear will always find “reasonable” justification for holding on to their cash. They are alternately waiting for clarity or a correction. People caught in this conundrum will usually only capitulate and invest at the peak of the cycle. Rinse and repeat.

What’s a person to do? Much like the old saying that suggests not yelling at one’s spouse unless the house is on fire, investors should never make an important decision when they feel fearful, angry or even euphoric. Every investor should have a plan and reason for owning their investment assets. Understanding one’s risk tolerance and employing an appropriate asset allocation is key. These simple steps will help the investor to avoid the bad choices that result from an investment style that is driven by emotion as much as anything else.

The Outlook

Many still see big scary things on the horizon. The fiscal cliff concerns have been replaced by debt ceiling scares. We would caution our readers to remember that most of what politicians say is designed to influence sentiment about them or their party. Any corrections in the stock market due to political wrangling have been temporary in nature and usually have provided a buying opportunity for investors. This debate may capture significant media attention, but should not be viewed as reason to do anything with one’s portfolio.

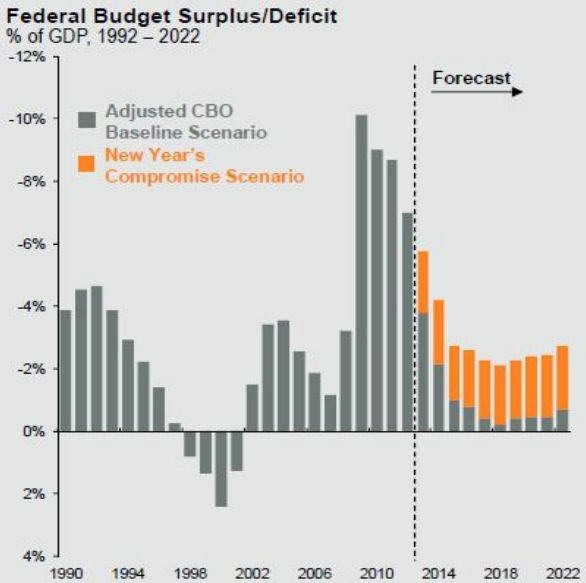

Another big scary thing is the U.S. budget deficit. Many “experts” will try to create a sense of crisis for this perceived problem. Many analogies are made to a household which must pay its debts and cannot spend more than it earns indefinitely. Unlike a household, the U.S. government can print more and borrow lots of money at very low rates. Also, because the U.S. dollar is still the primary reserve currency for the world, we find it hard to imagine that central banks will quickly replace their U.S. dollar reserves with anything else. The chart below shows a reasonable future scenario where the budget deficit improves quite quickly to normal levels. What is not likely is the deficit “spiraling out of control,” as many commentators are cautioning.

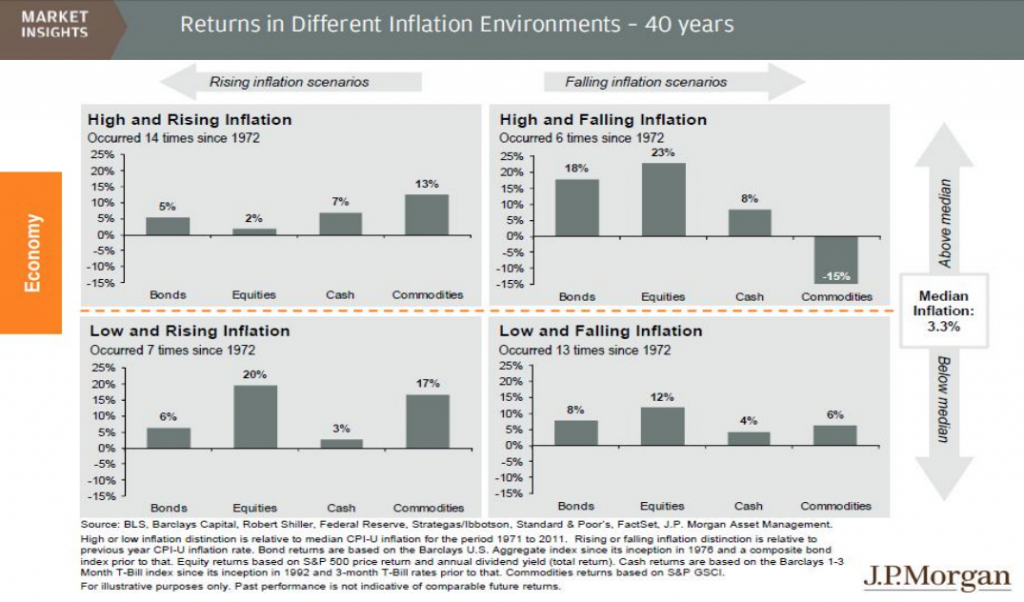

Sometimes we hear that inflation is bound to roar back at any minute and wreak havoc on the capital markets. While we understand the rationale for this forecast, we would note that it’s been out there for more than five years. Also, inflation rarely becomes a problem without tightness in the labor market and/or high capacity utilization, neither of which we currently see.

Thanks to the good folks at J.P. Morgan Asset Management, we have a useful graphic that shows what happens to asset returns under different scenarios of inflation.

We would submit that the most likely scenario going forward would be that of the lower left quadrant “low and rising inflation.” We can see that if this were to happen, investors can reasonably expect attractive returns from their stock portfolios.

Many of the key factors we use to assess the state of the capital markets remain mostly positive. U.S. economic data is still mixed but trending upward. We can expect some noise from the fiscal cliff and Hurricane Sandy in the Q4 numbers, but gradually improving data would not be surprising. Corporate profits continue to grow; consensus expectations look for another record year in 2013. Europe will continue to be a drag on the global economy for most of the new year, but not forever. We still think that the emerging market economies are likely to continue to grow. The U.S. Federal Reserve remains committed to keeping interest rates in place for the foreseeable future.

The only bit of concern on our radar screens is a pick-up in individual investor sentiment. As one may recall, negative investor sentiment is generally positive for the market. When sentiment turns positive, we tend to worry a bit. The strong rally in early January has led to an $18 billion net purchase is U.S. stocks and ETFs. One week’s data does not make a trend, but it’s the only thing keeping us from being wildly bullish on stocks.

As always, we don’t know for sure what’s going to happen over the next 6 months or 12 months, but we do know that many stocks are trading at attractive discounts to their fair value. We also know that equities have always afforded the best returns of any asset class over time. We also know that many people are still using fear as a key element in their marketing efforts to peddle their products. As long as fear remains prevalent in the eye of the public, we are likely to remain constructive on the stock market.

Sincerely,

Wolf Group Capital Advisors