The U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has been raging a battle against Coinbase[1] to obtain the identities of users of convertible virtual currencies (CVCs), like Bitcoin.[2],[3] This battle is being closely watched worldwide, as it touches on hot button issues—privacy of Bitcoin holder accounts, U.S. income taxation of CVCs, and international informational reporting of CVCs, to name a few.

More troubling, CVCs have been used for a host of illicit and illegal activities.[4] The message from the U.S. Government is clear: the Department of Justice, Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, and the IRS will continue to monitor this area very closely and tighten their enforcement net.

In this blog post, I thought I would summarize everything we know to date about CVCs from a U.S. tax perspective. Then, I’ll explain why CVC users should care about the IRS’s recent measures to obtain the identities of CVC users.

A Brief History of Convertible Virtual Currencies (CVCs)

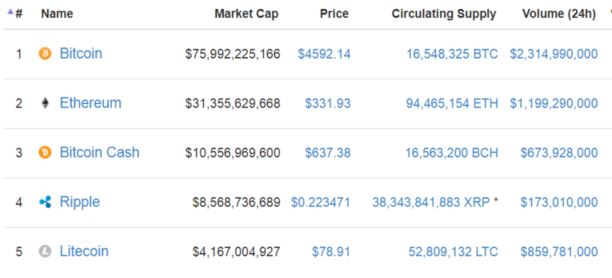

To begin, let’s go over the history. CVCs were created by a person or group of people called Satoshi Nakamoto on Halloween 2008.[5] The first CVC network was released to the general public in January 2009, and CVC users are now estimated to number between 2.9 and 5.8 million worldwide.[6] Although there are hundreds of types of CVCs on the market, the most commonly known are Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Bitcoin Cash. For other CVCs, the details on potential valuation, circulating supply, and other matters are less widely known.

The Top Five CVCs

To help provide clarity, here is a snapshot of the top five currencies courtesy of CoinMarketCap:

U.S. Tax Issues Raised by CVCs

From a U.S. tax perspective, as the use of CVCs has become more mainstream, two big questions have arisen:

- How will CVCs be taxed under U.S. law?

- What type of international informational reporting (if any) is required for individuals, businesses, or trusts that hold CVCs in foreign financial accounts?

How will CVCs be taxed under U.S. law?

First, let’s look at the U.S. income tax consequences. Surprisingly, the IRS has provided guidance via Notice 2014-21 on this topic, and it is quite extensive. In addition, both the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration[7] and the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network[8] have done so, as well.

Here are the big picture takeaways from the IRS on how convertible virtual currencies are taxed:

- Convertible virtual currency (CVC) is property.

- CVC has a value when you acquire it (i.e., basis) and value (i.e., fair market value at the point of sale) when you sell it.

- The gain or loss can be capital or ordinary. The test here is whether you have a capital asset.

- CVC is not a currency. So, there are no foreign currency gains or losses. But note here that the IRS specifically says, “Under currently applicable law…” This could be subject to change in the future.

- “Mining” CVC is an income recognition event.

- Receiving CVC for the sale of goods or services is an income recognition event.

- If a business pays an employee in CVC, then it is considered taxable wages. The business is also subject to informational reporting, i.e., a W-2 reflecting the CVC wages. There are pros and cons[9] to using CVC for payment to employees.

- If a business pays an independent contractor in CVC, then it is considered taxable self-employment income. The business is also subject to informational reporting, i.e., a Form 1099 reflecting the 1099 income.

What type of informational reporting (if any) is required for CVCs in foreign financial accounts?

Now, let’s take a look at international informational reporting. The two big areas to consider here are FinCen Form 114—also known as the FBAR or Foreign Bank Account Report—and Form 8938. These are the primary forms that must be filed in the U.S. if you have foreign financial assets.

If you are not familiar with the nuanced definitions of the types of assets that must be reported on these forms, I recommend that you first glance through this quick primer.

What type of financial asset are CVCs?

For FBAR and 8938 purposes, the best way to understand reporting of CVCs is to use the analogy of gold or precious metals.

When gold or precious metals are held directly in an offshore location, they are not reportable on the FBAR or 8938.[10] But, if there is a contract with a foreign person to sell assets held for investment, such as precious metals or gold, now you have a reportable asset on Form 8938.[11]

Additionally, if you have an interest in a foreign financial account that has holdings in gold or precious metals, you may also have an asset reportable on the FBAR. An example of this is a foreign physically backed exchange-traded fund (ETF) in precious metals, such as gold or silver, which would be a reportable account on the FBAR.

Does it make a difference how CVCs are held?

How are CVCs held? From what I understand (and I am not an expert on this), there are two ways for a person or entity to hold CVCs. The first is a paper wallet. The paper wallet contains copies of the public and private keys that provide the address of your CVC wallet and allow other CVC holders to send CVCs to the wallet.[12] In essence, you have transferred all of your CVCs to paper, and just like directly holding or carrying a brick of gold, you do not have a foreign financial asset that is reportable on the FBAR or 8938.

Second, you can hold CVCs via a virtual wallet. Here is where the analysis gets nuanced. There are literally hundreds of companies that offer virtual wallets.[13]

Here is a brief run down:

- Coinbase Mobile Bitcoin Wallet[14] – Location: United States

- Ledger Wallet[15] – Location: France

- Mycelium Wallet[16] – Location: Cyprus

- Airbitz Bitcoin Wallet[17] – Location: United States

- Blockchain Wallet[18] – Location: Luxembourg

Why it matters where your virtual wallet (company) is located

The location is important.

If you use a wallet from a company located in the United States, you would not have a “foreign financial account” because the virtual wallet is located inside the United States. Therefore, there is no FBAR or 8938 reporting requirement.

But for the wallets located in France, Cyprus, and Luxembourg, you can make an argument that these meet the definition of reportable financial account for the FBAR as either a bank account, securities account, or other financial account (catch-all). There is obviously a financial interest if the owner is a U.S. person because that person is the owner of record for the CVC. If the value of the CVC at any point during the year exceeds $10,000—or if the maximum value of the CVC in aggregate with the maximum value of any other foreign financial accounts exceeds $10,000—then you likely have an FBAR filing requirement for the CVC virtual wallet.

What about the 8938? Do we consider the CVC held in a foreign virtual wallet a specified foreign financial asset? I think the conservative answer here is yes. It would likely be classified as a financial instrument.

Additionally, if there is a contract by a business to deliver CVCs in a foreign virtual wallet in exchange for future goods or services, there again you may have a specified foreign financial asset.

The key here is to track the location of the virtual wallet. From there, I would apply a very conservative interpretation as to the requirements for a reportable financial account under the FBAR and a specified foreign financial asset under Form 8938.

WHAT IF USERS DO NOT REPORT THEIR ACCOUNTS?

This is where we come full circle. I started this blog post by mentioning that the IRS has gone to battle to obtain the identities of users of CVC accounts. That battle has progressed to the point of issuing a John Doe summons in November 2016.

Now that we have covered a bit of CVC history and tax treatment, I’d like to explain why the IRS’s recent actions are so important.

What many CVC users may not fully grasp is that more than their privacy is at risk.

If the IRS succeeds in obtaining the identities of CVC users via the John Doe summons, the IRS would easily be able to determine whether Bitcoin and other CVC users had properly reported income on their tax returns.

Chances are that most users have not done all the proper reporting. This means a lot of low-hanging fruit for the IRS—especially at a time when their budget is tight.

Should the IRS identify a significant amount of unreported income, the U.S. Treasury Department may use this victory to ask for John Doe summonses on offshore virtual wallet companies. This, in turn, would lead to individual reporting issues for the FBAR and 8938.

What happens if you don’t report CVCs on the FBAR or 8938?

The price is steep for those who “willfully” fail to report foreign accounts:

- Failing to report can be a criminal violation, resulting in jail time

- The standard willful penalties are $10,000 or $100,000 (see index-adjusted amount) per unreported account (or 50% of the maximum account balance)

These penalties add up quickly, and they apply whether or not the CVCs were used for illicit purposes.

What if CVC users were unaware of the reporting requirements?

Unfortunately, being unaware of the requirements is not a viable defense. In 2014, when the IRS issued Notice 2014-21, this effectively provided notice “to the world” of the type of income associated with CVCs and how a taxpayer should report them. The notice made the information public knowledge subject to a duty to inquire on behalf of the taxpayer.

Is there any relief for CVC users if CVC income and accounts have not been properly reported?

Since 2009, the IRS has offered a variety of amnesty programs (see Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Programs) for those who have failed to properly report their foreign assets and income. Several programs are currently available but could be terminated at any time. The amnesty program options and penalty rates depend on multiple factors, including whether the improper reporting was willful and an individual’s geographic location and circumstances.

One catch: relief is not available once the IRS flags an individual or institution

Amnesty programs can offer some relief from penalties, but they are only available if individuals come forward before the IRS has them on its radar.

That’s why the IRS’s current battle is so important. If the IRS succeeds in obtaining the names of Coinbase’s CVC account owners via its John Doe summons, and it identifies a large amount of unreported income, then that success might embolden the Treasury Department to seek John Doe summonses on offshore virtual wallet holders.

If this were to happen, then the CVC users of the virtual wallets would become ineligible for any relief, similar to the clients of Sovereign Management.[19], [20]

Since many CVC users likely have not been fully compliant with tax and account reporting requirements (whether or not the accounts were used for illicit purposes), they become easy targets for the IRS and significant potential targets for the Department of Treasury’s Offshore Compliance Initiative.

[1] https://www.coinbase.com/?locale=en-US

[2] https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/court-authorizes-service-john-doe-summons-seeking-identities-us-taxpayers-who-have-used

[3] https://www.forbes.com/sites/kellyphillipserb/2017/09/05/irs-responds-to-privacy-other-challenges-in-bitcoin-records-fight/#4738dfdb65aa

[4] https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/assistant-attorney-general-leslie-r-caldwell-delivers-remarks-aba-s-national-institute

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bitcoin#History

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bitcoin#History

[7] https://www.treasury.gov/tigta/auditreports/2016reports/201630083fr.pdf

[8] https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/shared/FIN-2013-G001.pdf

[9] https://www.accountingtoday.com/opinion/can-employees-be-paid-in-cryptocurrency

[10] https://www.irs.gov/businesses/comparison-of-form-8938-and-fbar-requirements

[11] https://www.irs.gov/businesses/corporations/basic-questions-and-answers-on-form-8938#CashQ5

[12] https://www.coindesk.com/information/paper-wallet-tutorial/

[13] https://www.cryptocompare.com/wallets/#/overview

[14] https://www.coinbase.com/mobile

[15] https://www.ledgerwallet.com/

[16] https://mycelium.com/mycelium-wallet.html

[19] https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/court-authorizes-service-john-doe-summons-seeking-identities-us-taxpayers-who-have-used-debit

[20] https://www.irs.gov/businesses/international-businesses/foreign-financial-institutions-or-facilitators