If you are an individual who owns or holds at least a 10% interest in a Controlled Foreign Corporation (CFC), you have probably spent the last 4 to 6 weeks working your CPA on how to calculate the new Repatriation Tax[1] under the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) §965. By April 17, you paid the Repatriation Tax in full—or one-eighth of the tax due under the 965(h) installment plan.

You may be under the impression that everything now goes back to normal.

Unfortunately, that is incorrect and represents nothing more than a false sense of security. Instead, you may be positioned for a large ongoing tax hit. The good news is, a few planning steps now could help you significantly reduce the annual impact.

The payment of the Repatriation Tax with your 2017 tax return transitioned you into the new U.S. system of international corporate taxation, and that game has just begun. As of today, the IRS has yet to release notices, guidance, or regulations related to certain aspects of the new system, and individual owners of CFCs must now concern themselves with learning and understanding how the following provisions will impact their foreign corporations: IRC §951A, §962, §245A, §246, and §250.

Although the Repatriation Tax transitioned you to the new system, you are likely still structured for tax efficiency under the old system.

U.S. International Corporate Tax (1962–2017)

The old system of international corporate taxation, called deferral, was enacted in 1962. Under this system, foreign corporations could defer earnings until one of three things happened:

- Subpart F Income was triggered,

- Dividends were paid, and/or

- A §956 inclusion was triggered.[2]

Most individual owners of CFCs may have taken steps to plan their operations to not trip the Subpart F and §956 traps. If no dividends were ever issued, then individual owners likely have had a history of filing Form 5471 as a Category 4 and 5 filer. This “informational” filing is just as it sounds. Information about the foreign corporation is provided, including the profit and loss statement, balance sheet, and retained earnings.

If you polled most tax professionals who deal with individual owners of small CFCs in early 2017, they would have uniformly responded that the form has had little to no impact on their clientele other than informational reporting[3]—that the form did not have a tax effect, at least not until IRC §965 was introduced for the 2017 tax return. Deferral came to an end with the new tax legislation, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which was passed in December.

U.S. International Corporate Tax (2018–Current)

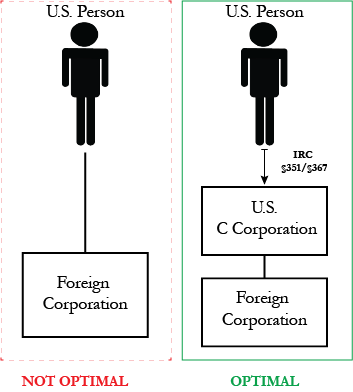

The new system of international corporation is called “Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income” or “GILTI.” This system was designed for a U.S. multinational company (USMNC)—i.e., a U.S. C corporation that has offshore subsidiaries—not for individuals who have direct ownership in foreign corporations.

Although not designed for individuals with direct ownership, GILTI now applies to them, and unless those individuals make changes in their ownership structure, they risk being taxed at high rates on income that was formerly not considered under the deferral regime.

The GILTI system of taxation is similar in its design to an alternative minimum tax. At a very high level, because we no longer have deferral, GILTI will tax the operating income of controlled foreign corporations on an annual basis.

Here is how GILTI works for a USMNC:

So, if a USMNC is subject to GILTI, the (“minimum”) tax is 10.5%.

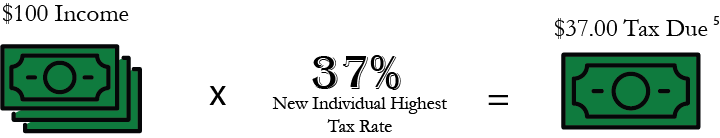

Here is how GILTI works for an individual person:

The tax differential between the USMNC and individual person is 26.5%. That is a big gap. So, what can be done? The answer is GILTI planning. And if you have not already started this process, you need to start now.

Since deferral provisions no longer apply, you need to consider restructuring for tax-efficiency under the new system.

GILTI Planning

Planning for GILTI boils down to the following steps:

Step 1 – Gather all the relevant data needed for your foreign corporation

- 2018 year-to-date revenue

- 2018 projected revenue

- 2018 year-to-date expenses

- 2018 projected expenses

- Foreign jurisdiction corporate and dividend tax rates

- Fair market value of all the tangible property of the business

Step 2 – Run the scenarios

- Scenario 1 – GILTI

- Scenario 2 – GILTI, plus §962 election

- Scenario 3 – Transition the individual person owner to a U.S. C corporation (micro-multinational)

Step 3 – Discuss the next 3–5 years

- Expansion of the business earnings

- Expansion into other foreign jurisdictions

- Expansion into new business offerings

- Repatriating the retained earnings back to the U.S. vs. keeping the retained earnings in the foreign jurisdiction

Step 4 – Harmonize Steps 2 and 3 and pick a scenario from Step 2

Step 5 – Implement

The implementation step is the most critical. For example, if you were to pick Scenario 3 (under Step 2), then you are on a timeline clock of 366 days[4] from the moment you transition your stock to the C corporation before you can make a dividend. There are also practical considerations. You must register the corporation, create a bank account, draft corporate documents, prepare for the transition from filing one individual tax return to filing both a C corporation return and an individual return, and update your current estate plan.

If you know you have this issue or think it may be an issue for your CFC, then I strongly urge you to get started on GILTI planning now while you can still make a difference on your 2018 tax bill, i.e., plan now and pay less. The summer is the perfect time for most tax professionals to walk you through these calculations.

How do I find out more? Our recent blog post by International Tax Director Mishkin Santa provides further details on the Repatriation Tax, as well as contact information should you have questions relevant to your situation.

Mishkin Santa is an International Tax Director at The Wolf Group, P.C., specializing in cross-border tax matters.

Mishkin provides both consulting and compliance services to foreign nationals, U.S. citizens, and other U.S. tax residents (individual and corporate) on international taxation issues, including Offshore Voluntary Disclosures, Exit Tax planning, pre-immigration planning, pre-retirement planning, foreign pension analysis, foreign trust taxation, expatriate taxation, and International Organization employee taxation.

This material is for informational purposes only and does not constitute tax or legal advice. Please consult your own tax or legal advisor before engaging in any transaction.

[1] Also known as the “Transition Tax,” or the “Toll Charge”

[2] Tangentially, we also have the transfer pricing regime under IRC §482.